Sometimes a trick shot is the result of asking “What happens?” What happens if I draw off this ball, can I sink this other ball? What happens if I hit these two balls that are touching each other? The premise is that you look at a situation and explore the result.

Sometimes a trick shot is the result of asking “What happens?” What happens if I draw off this ball, can I sink this other ball? What happens if I hit these two balls that are touching each other? The premise is that you look at a situation and explore the result.

For my SQL “trick”, I asked “what happens if you update a value to the same value?” It’s a question that gets asked by a lot of folks, but I wanted to explore the tools in SQL Server to answer that question for me. We can read about someone else figuring this out, but I think my best learning is done when I puzzle out a problem on my own.

I created two simple scenarios: an update of a column to itself and an update of a column to itself plus one. Fairly simple stuff:

create table test (cola int not null identity (1,1), colb int not null default 0, colc varchar(100), constraint pk_test primary key clustered (cola)) insert into test(colc) select top 1000 a.name from sys.objects a,sys.objects b --Reset, write all pages out from buffers checkpoint dbcc dropcleanbuffers --These tests need to be run separately! --Test 1 update test set colb = colb --Test 2 update test set colb = colb+1

(Note, the checkpoint and dbcc dropcleanbuffers is to make sure I’ve cleaned out all my log activity before I run either test.)

My first actual stop was to use DBCC PAGE to see if I could see if looking at the raw page would show if the pages had been modified. Unfortunately, this information wasn’t there, though I did get a lot of exposure to reading the output of the command. Not sure where to go next, I reached out to the Twitterverse on #sqlhelp. I was directed towards two items:

- sys.fn_dblog – Undocumented function that shows all the individual actions in your transaction log.

- sys.dm_os_buffer_descriptors – DMV that lists information on all the pages in your buffer pool

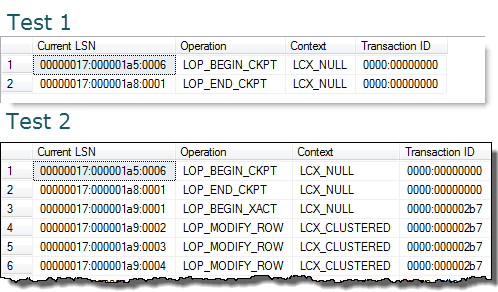

Querying both of these tools gave me the answer to “What happens?”, but in two different ways. When I looked at sys.fn_dblog, I could see no actual transactions when I updated the column to itself, but a transaction for each update when the value was actually modified:

--check for log activity select [Current LSN],Operation,Context,[Transaction ID] from sys.fn_dblog(null,null)

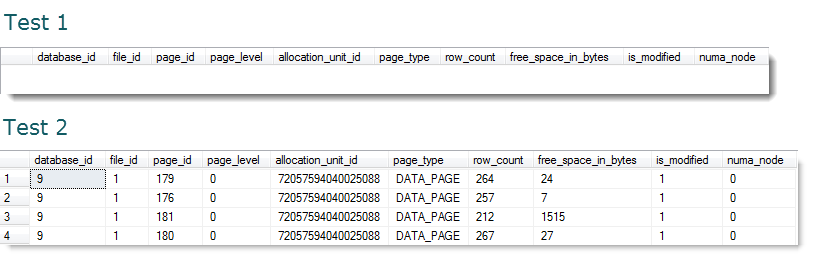

Sys.dm_os_buffer_descriptors has a field labeled ‘is_modified’ which is set to 1 if the page has been changed. When I queried for pages with is_modified equal to 1, I saw further evidence of what fn_dblog showed me:

--List pages in the pool that are modified

select * from sys.dm_os_buffer_descriptors

where is_modified = 1 and database_id = db_id('junk')

In both cases, I was able to see clearly what was going on under the covers and that SQL Server is actually intelligent enough to save some work when no work is actually being done.

Of course, the funny thing about trick shots is someone usually can do it better. Shortly after I figured this all out on my own, I found this fantastic blog post by Paul White (b|t) showing all this with a little more detail. However, what’s important is what you can learn by doing things yourself. It may take you time to reinvent the wheel (something you might not be able to afford), but when you do it yourself you learn a lot about how a wheel works.

Thanks for joining me this month, where I not only get to contribute but also host T-SQL Tuesday. I’m excited to see what other things our peers can teach us about the things they’ve learned by playing around with SQL Server, trying to see “What happens?”

I’m tweeting!

I’m tweeting!